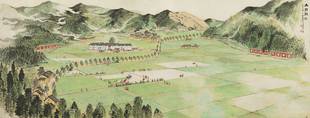

Chinese Painting

Chinese painting is closely related to writing or calligraphy. Most paintings are enriched with verses or with observations of man in nature. Done either on silk or paper, it has three principal formats - the vertical hanging scroll, the horizontal handscroll, and the small album-leaf, which may be square, round or fan-shaped and framed on silk.

Calligraphy is the art of writing beautifully, generally in freehand, with pen or brush on paper or any similar material. Calligraphy is used in countries using the Arabic scripts, calligraphy is used in creating real works of art.

The Chinese technique in painting also invites contemplation. The emphasis is on rhythm in line, harmony in color, precision in form, and balance in structure. Chinese outlines are as subtle and lithe as silken thread, but there hovers around them an air of finality, continuity and unity. Brushstrokes can be pointed without being weak, powerful but not stiff, rounded but not like balls of fur, square without corners, almost straight but not quite. The use of overlapping or backstepping edges summarizes a neat three-dimensional effect.

Qualities of Chinese Painting

What makes Chinese painting completely different from every other school of painting in history, except its own pupils in Japan?

1. Its scroll or screen form

2. The Chinese scorn of perspective and shadow

3. The exclusion of color

4. Skills in execution lying almost entirely in accuracy and delicacy of line, not on the power of perception, feeling and imagination.

5. Emphasis as an indirect suggestion as against explicit representation - suggesting not describing.

6. Men rarely being the center or the essence of the picture.

7. The love for flowers and animals as subject for painting. Sometimes these were symbols like the lotus and the dragon, but after they were drawn for their own sake, the charm and mystery of life appeared as completely in them as in men.

8. Often men shown as old, and nearly all alike. Seldom did the painter look at the world through the eyes of the youth.

9. The sincerity of the feeling for nature.

Chinese painting sought to suggest than to describe. It never cared for realism. Form was everything, and the subject was anything.

Chinese Architecture

Architecture has been a minor art in China. Large structures have been rare, even in honoring the gods, and only a few pagodas date back beyond the sixteenth century.

In later years, the pagodas dominated the landscape of almost every Chinese town. Communities erected pagodas in the belief that such structures could ward off wind and flood propitiate evil spirits, and attract prosperity. Usually they took the form of octagonal brick towers rising on a stone foundation to five, seven, nine or thirteen stories, because even numbers were unlucky.

Like the Indian stupa, the pagoda served to house Buddha's relics, realizing a religious symbolism in its structure, as described in the following quotation:

The ascending sections were taken to represent the many terraces of the mythical world mountains. Since the relics in each floor were imbued with potency and mysticism, the whole building became as spiritual as the mystic mountain. It was at first merely objectifying. The great pillars that run up the core of the pagoda building represents the invisible axis that joins the centers of heaven and earth. And the many heavens of the gods are symbolized by the disks, and sometimes globes, spindled by the long thin spire standing on the pagoda's roof.

One of the most famous pagodas was that built by the Ming Emperor Yung Lo in 1431 at Nanking. Called the Porcelain Pagoda, it was an octagonal structure ornamented with three-color porcelain and a large gold ball surmounting the roof.